Old Sydenham

Jan Piggott traces the connections between the Wynell-Mayow sisters and their friend, the poet Thomas Campbell of Peak Hill.

For Steve Grindlay, with admiration and affection

Sydenham

Mayow, Wynell, Dacres, Adams’Rill – Mayow family names on the London A-Z

I have lived in Sydenham for more than forty years. Life in bygone days has always engaged my ‘escapist’ imagination; I was curious to learn, from various sources, how the land and buildings here lay in earlier days and to people it with scraps of information about interesting former residents. To me the most fascinating historical period of our locality is that of its former prosperity, the nineteenth century. Characterful individuals and families (the Shackletons settled here, from Dublin, for example) trod these pavements, or were visitors – on foot, on horseback, in carriages, on early steam trains (at first with seats in open trucks). In the latter half of the century, of course, millions came, to see the world-famous Crystal Palace and Park.

The street name Perry Vale, deriving from the word pear, tells us about its former orchards; among a vale landscape of fields, hedges, stiles, gates, cart-tracks and hamlets, there were a few roads and villas with gardens. Built up, sub-urban, Sydenham in 1889 was officially sub-sumed in ‘Greater London’. We live now in SE23 or SE26 and off the South Circular Road, but once upon a time when one left the Metropolis, passing through Dulwich (at that time in Surrey), and crossing the heights of Norwood (ancient North Wood), or descending Forest Hill, it was right here that one set foot on a fertile plain that was actually in Kent (until 1889), just within the boundary. Green and pleasant, a vista of the Garden of England extended for miles beyond. We learn from A Descriptive Account of Sydenham (1878) by Mayow Wynell Adams, JP (1808-98; effectively our last squire) that ‘the soil of Sydenham was very productive of fruit trees‘, and that cider was made from the orchards. Sydenham Common and Penge Wood were still famous for melodious nightingales in the 1830s and 1840s.

From 1854 below the Hill the population increased dramatically, as a dormitory for London, but mostly because the mansion and demesne of Penge Place had been transformed into the Crystal Palace and Park. Musicians and many cultivated families chose to live nearby, and the Palace was exciting with ambitious displays, events, concerts: on a high wire Blondin, acrobat of genius, very many feet above a seated audience, having carried a stove on his back to the middle, cooked an omelette which he steadily lowered to them on a tray (with two full wine glasses); on the Terraces the Brock family mounted pyrotechnic spectacles (their speciality was huge ‘set pieces’, often of patriotic events, animated by men in asbestos suits wearing live fireworks, anticipating the earliest silent ‘movies’). Visitors walked up the Avenue from Sydenham station or arrived at the two dedicated Palace railway stations: the (now demolished) ‘High’ and the ‘Low’ Level.

Mayow family

In 1800 the largest private estate belonged to the hospitable Mayow family in their prime, hosts to a wide circle of friends, including celebrated artists, writers and politicians of the day. They were enlightened squires for almost a century; all the land between Sydenham Road and Perry Vale was theirs – not just ‘Mayow Park’. They helped to endow St Bartholomew’s church, schools and eventually the Park. Wynell Road and obviously Mayow Road, but also Adams’Rill and Dacres Roads, in fact memorialise the family; meanwhile, probably in careless ignorance, we keep their names alive daily in our speech and thought negotiating our thoroughfares. All derive from Mayow family names. The Wynells and Mayows were originally west country clergy and gentry.

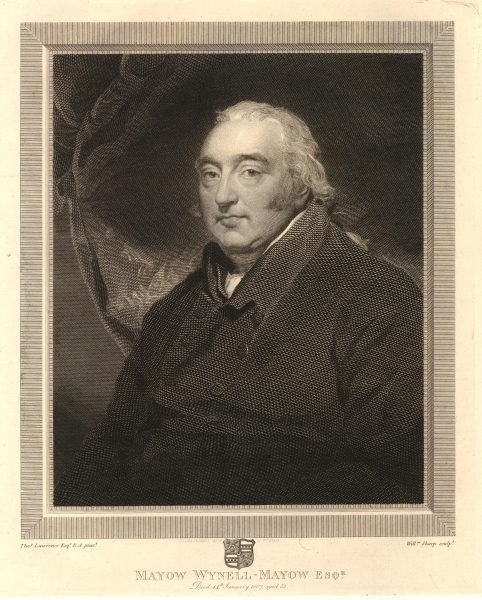

Mayow Wynell Mayow (1753-1807)

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Mayow Wynell Mayow (1753-1807) of Montagu Street in London, bought the ‘Old House‘ at Sydenham, with its rather boring name, and its bosky estate, as his country house in 1787.

Mayow was a civil servant, a solicitor in the lucrative Excise Office. Spoken of as a man of integrity, and ‘venerable’ in old age, he is also alleged to have been one of those Chancery officers who took advantage of his position in the course of his work to buy up land cheaply. He and his family planted remarkably fine trees – outside the boundary of the Park a good number also survive. (Inside the Park, however, note that the groups of magnificent oaks are much older, and in rectangular relation to each other rather than according to the Mayows’ picturesque early nineteenth-century curving landscape gardening principles.)

Mayow’s wife Mary was the daughter of a Londoner. They had no male heir; their five daughters were celebrated in their day for intelligence, refinement, and affection. Elizabeth married William Dacres Adams, who inherited the Old House from her father: he was Private Secretary to two Prime Ministers (Pitt the Younger, and the Duke of Portland), and from 1811 until 1834 a Commissioner of Woods and Forests; his mother was a Dacres, from a landed Leatherhead family; Anne married an aristocratic MP, and Caroline (somebody called her an ‘angel without wings’) a vicar. Mary, the eldest daughter, and thus ‘Miss Mayow‘, and Frances (or Fanny) never married.

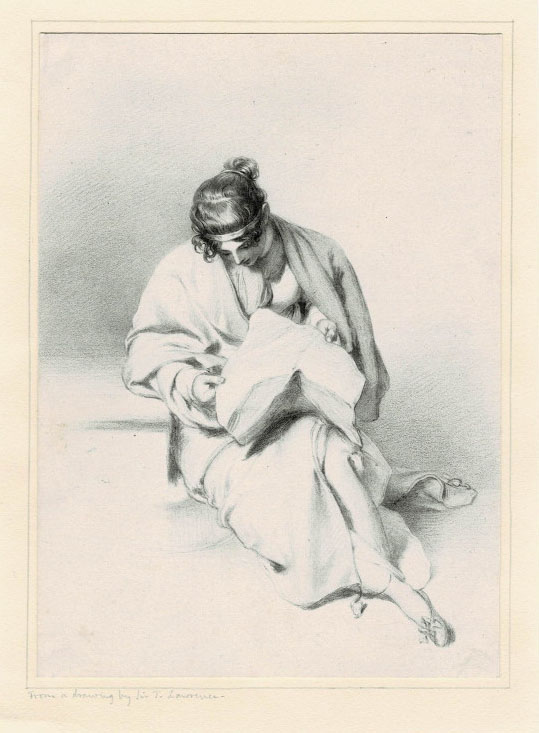

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Mayow Park came about when Fanny died in 1874 at the age of 91, and it was her nephew Mayow Wynell Adams, the historian of Sydenham and the last inheritor of the estate, who sold the 17½ acre Park (first known as the ‘Recreation Ground’) to the Lewisham Board of Works for half its market value. At his own death, the Old House was pulled down and the very well-designed and built houses on the Thorpes Estate were put up on the site of the house and its immediate gardens, from 1901 to 1914. The layout, circuits and trees of Mayow Park still assert Regency landscaped charm, slightly compromised by new torture-gym machines in bright chemical colours.

The Old House, with its valuable collection of English, Dutch and Flemish paintings, fronted the present Sydenham Road behind a wall and a great gate.

Here the lively and cultivated Wynell-Mayow girls grew up, fond of reading, music, and serious conversation. They grew mulberries in their garden; their dog was called ‘Beau’. Sir Thomas Lawrence, President of the Royal Academy, and the wit Sydney Smith were ‘frequent guests’.

Sydenham springs and wells

In 1838 Christopher Greenwood described the Old House in An Epitome of County History, Volume 1, Kent (p 25):

‘At Sydenham are the noted medicinal springs, commonly called, from their proximity to Dulwich, “Dulwich Wells“, the waters of which possess the same cathartical qualities as the Epsom waters. They were discovered about the year 1640.

Here also is a considerable MANSION, with extensive grounds, well wooded and neatly laid out, the property of the Misses Mary and Fanny Wynell Mayow. The house appears to have been erected about the year 1660, and probably is the only building of any consequence in the place. It has been partly modernised, and is seen to the greatest advantage from the north. The interior, which is spacious and convenient, is decorated with paintings by Cuyp, Zoffany, and Vanderheyden*; and several portraits and drawings by Sir Thomas Lawrence, Jordaens, etc’.

*[This is surely a mistake for Verheyden]

By cathartical the author means that the waters relieved constipation, which is why George III used to attend Sydenham Wells. On one visit a large military review with a sham fight at Peak Hill on Sydenham Common was organised for him, watched by some of the princesses in open carriages.

The Custodian of the Well was ‘old Betty‘: too large at death for any hearse, she was carted to Lewisham for burial. The Mayow daughters also recalled ‘a woman called Neville, dressed after the manner of a Shepherdess in a Pantomime crook and all, with red petticoat and high-crowned pointed hat, who fed her flock on Sydenham Common. ‘She lived in a hut near The Dolphin pub.

Of the Sydenham springs and wells which rise in the hilly slopes above us, one underground stream still surfaces in Peak Hill in runlets, then dives underneath the railway track and Silverdale, from time to time springing up in grassy areas of the Park after heavy rainfall; I have seen it come up through tarmac on Silverdale. In the days of the Mayow family the stream then emerged beyond the Park and ran down above ground as a ‘rill’ ( = stream). This was known as Adams’rill after William Dacres Adams, the second Mayow family squire. Adamsrill Road is pleasing to drive down: fairly steep, it bends with a natural contour more like the channel of a watercourse than a surveyor’s straight line.

Some young entrepreneur should bottle our genuine, historic, organic, Sydenham Wells Cathartic Waters, ‘locally sourced’, and persuade our many Sydenham Road chemists’ shops to sell it for the relief of costive locals. (Luckily, the chemists could say that Mayow Wynell Adams remembered the Well as ‘dirty,’ and the waters ‘very nasty’.)

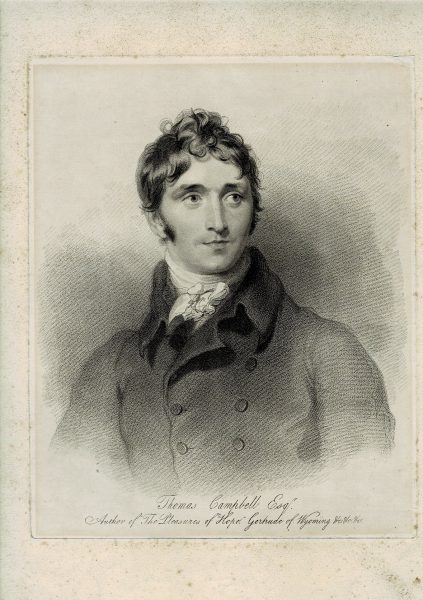

Thomas Campbell

© The Trustees of the British Museum

We learn something of the personality of the good-looking Wynell-Mayow sisters and of their ‘elegant society’ from surviving records of their warm friendship with Thomas Campbell (1777-1844), the young Romantic poet from Glasgow, then in his 30s (later a famous journalist, editor, lecturer and Lord Rector of Glasgow University). Campbell rented a six-room semi-detached ‘cottage’ on Peak Hill on the Common with his wife in 1803, at the age of twenty- six; they lived there, with two young sons, until 1821. The Common at that time was described by a biographer as ‘beautiful and furzy, tree-fringed, with shady lanes and wide prospects’.

Long extracts from many lively letters Campbell wrote to Mary and Fanny were published shortly after his death. His biographer tells us the poet, ‘in almost daily contact with congenial minds’, would consult the family ‘with advantage, on matters of taste’. Their ‘friendly efforts to promote his best interests had awakened in his ever grateful heart, a feeling of respect and affection’. His Sydenham years Campbell acknowledged as the happiest of his life, having much to do with their friendship. Though he was dogged with anxieties over his own and his family’s health and his modest income, writing to the Mayow sisters he said that Sydenham ‘seemed the sweetest spot in the world, in spite of many sorrows’, indeed ‘the greenest spot in memory’s waste’; he added, ‘I saw your dear nephews, William-Pitt and Dacres, today thriving, like my own sweet boys, on this invigorating air’.

© Lewisham Archives

Campbell on most afternoons spent an hour at the Old House. Together they read Milton, Spenser, Cowper, and James Thomson. He wrote a ridiculous poem for Mary rhyming Mayow with Galileo (something that cost him ‘a world of pangs and scratchings’):

Beside that face, beside those eyes

More fair than stars e’er traced in skies

By Newton, or by Galileo,

Oh, how couldst thou, altho’ a brute,

Upon that face when gazing mute –

How couldst thou crush the gentle foot

Of Mary Wynell Mayow?

‘Mary’, he wrote to Fanny, ‘will absolutely kill herself if she lives always in the excited state of making efforts about others’.

Though the girls were ‘thorough Tories’, Campbell recalled how his own ‘Whiggism’ was ‘as steadfast as it still continues to be’. He wrote that ‘this acquaintance ripening into friendship, called forth a new liberalism in my mind, and possibly also in theirs’. Campbell’s friends in town were the famous Holland House set of politicians, writers and intellectuals. Charles James Fox, former Prime Minister, with whom he discussed classics there, was known to be an admirer of his poems. Like William Blake, Campbell was strongly opposed to slavery and the exploitation of child chimney sweeps.

Fanny in particular comes alive from Campbell’s letters, as if she was someone of our own day we could know and understand. He wrote to Mary describing a visit he made to Fanny that morning, with a ‘long, delightful, wise and entertaining chat’… ‘I assure you, I never saw her more healthy, charming, cheerful: everything that is beautiful, and compared with her sometimes state of nerves, she is now positively brazen-faced!’ – He teased Fanny about her illegible handwriting.

A portrait in pencil Thomas Lawrence made of Fanny at the Old House in 1807 was lithographed in 1821 by Richard James Lane (above), showing her studying one of those large folded ‘broadsheets’ that constituted a newspaper of the day. Campbell wrote of Fanny,

I like her heart; ’tis warm to friends;

Her face I could not wish to vary;

And polished to her finger-ends,

Her form has something statuary.

Her taste – I’m vain enough to deem –

Is good, because with mine it tallies;

Her wit, I very much esteem

Save when my own dear self it rallies!

Poems

Campbell’s poems are mostly forgotten today, though he has three dense columns in The Oxford Book of Quotations, including ‘Tis distance lends enchantment to the view‘ from The Pleasures of Hope (1799). On Peak Hill at that time Campbell was composing a narrative poem, Gertrude of Wyoming (confusingly, Wyoming in Pennsylvania). This features a family of settlers. Being English, they were naturally determined

‘to plant the tree of Life’ – ‘to plant fair freedom’s tree.’

The settlers encounter both very good and very bad Indians; indeed Gertrude is mortally wounded in a sudden attack. Campbell was much mocked for introducing grossly false scenery and panthers into Pennsylvania. Having shared the Mayow sisters’ grief at the death of their father, he told them he had based the character of Gertrude’s father, Albert, on Mayow Wynell Mayow: they had in common ‘serenity in mature life’ when the obvious ‘fire, fervour, and sensibility’ of a worldly career had been ‘subdued and sweetened by reflection’.

On intimate terms with Thomas Lawrence he began a Life of the artist, but gave it up to write another that he completed of a second close friend celebrity, Sarah Siddons.

Campbell fervently espoused two causes arising from youthful German and Austrian travels and continental sympathies: the first was his very public and practical support for Polish independence, in his day twice brutally crushed by Russia. In The Pleasures of Hope, before his Sydenham days, he had already lamented the fall of their heroic champion Kosciuszco, wounded in the failed uprising against the Russians in 1794, fighting against partition of their country under Russia, Prussia and Austria:

Hope, for a season, bade the world Farewell

And Freedom shrieked as KOSCIUSZKO fell

In 1831 the Russians again brutally crushed an insurrection, driving thousands of Poles into exile. ‘Poland,’ he wrote, ‘preys on my heart night and day.’ Campbell was disgusted by the British government’s indifference; he fostered exiles and founded the Friends of the Polish Cause.

‘The Pleasures of Hope’. The Polish war hero, Kosciuszko, was wounded in a later skirmish.

In 1825 Campbell published a formal proposal in The Times for a secular University of London (based on his admiration for contemporary German academic institutions). This led directly to the founding of University College, for entry without compulsory membership of the Church of England.

Campbell’s literary friends visited him at Peak Hill, and he is said to have entertained to dinner at The Greyhound, a short stroll away from his cottage, in turn Walter Scott, Sarah Siddons, George Crabbe and Byron. Incidentally, he is said to have ‘detested’ the poetic ‘Lake School’ of Wordsworth, Coleridge and Southey. Byron, whom his host accompanied after dinner up to the junction of Sydenham Hill and Westwood Hill, on parting, mounted his horse (at our commuter roundabout by the Crystal Palace campsite), and throwing his hat up in the air, exchanged three cheers with his fellow poet.

Funeral

Campbell’s funeral in 1844 in Poet’s Corner at Westminster Abbey was attended by Sir Robert Peel, Disraeli, Thackeray and Macaulay. A Polish officer placed a handful of earth from Kosciuszco’s grave on his coffin. A thunderclap interrupted the service.

At St Bartholomew’s Church the Mayow family are commemorated in the churchyard by impressive tombs; inside with brass tablets. Mayow Wynell Adams in his history of Sydenham also indicates the carved capitals of the columns on the north-side, at the chancel arch, ‘adorned with busts (most of them good likenesses) of those who by what they have done for the church, deserve to be held in remembrance’. They are Queen Victoria, the Earl of Dartmouth (Brockley landowner), the Rev Henry Legge, the Rev Bowdler, St Bartholomew, and the author’s father, William Dacres Adams.

In 1900 at St Bartholomew’s the massy lych gate was dedicated to the memory of Mayow Wynell Adams, neatly bringing the century and this memorial of the family to rest. Next door to the church on the left lived Dr Shackleton and his ten children, and the following year, 1901, Ernest Shackleton, Third Officer in the Merchant Navy, was to be appointed Third Lieutenant on Robert Falcon Scott’s Discovery expedition.

Dr Jan Piggott FSA is the author of Palace of the People (C Hurst, 2004), about the Sydenham Crystal Palace. He was formerly the head of English and latterly archivist at Dulwich College.

Sydenham

April 2022

Top image: The Old House from the rear, with Mayow Park in the background